Conversation

Unlearning hierarchy at the Free School of Architecture

4/25/2019

Elisha Cohen, Lili Carr, Karina Andreeva and Tessa Forde

The Free School of Architecture is an experimental, tuition-free program founded in 2016 that brings architectural thinkers to Los Angeles for several weeks of participatory learning. Four of the original participants – Elisha Cohen, Lili Carr, Karina Andreeva and Tessa Forde – took over the project in 2017 and organized the 2018 edition, which is extensively archived on Are.na. We caught up with them via email to hear their thoughts on alternative education in art and design.

Leo Shaw:

How do you describe the Free School of Architecture when people ask? Can you tell us briefly how it came to exist in its current form?FSA Organizers:

Free School of Architecture is a collective and collaborative effort by four prior participants: Elisha, Lili, Karina and Tessa. Located in four cities in three different countries, the organizers used any free time available to brainstorm, conference call, make decisions, and eventually actuate FSA for the summer of 2018. We put together a pretty insane, six-week schedule of three to four sessions a day, six days a week, collaborating with over 55 different local organizations, individuals and advisors. Around fifty participants joined us in Los Angeles, some full-time and many part-time, throughout the summer. This tuition-free program brought together international participants with a focus on knowledge exchange and urban exploration of the city via collaboration with local groups and organizations. [The 2018 iteration] built on its inaugural session in the summer of 2017, organized by Peter Zellner, an architect and educator. While he brought together a group of people, he had no plans to continue with it. Mid-way through that summer, participants began to question what FSA should become in the future and took on organizational roles. At the end of that summer, the four of us decided to make another FSA happen the following year. We now own and run the organization. Based on our experiences as both participants and organizers, we are learning from these first two years to decide how FSA should manifest in the future.

We have taken an experimental approach from the beginning, knowing that it might fail. This experimentation, and the resulting evolution, is a core value for us. This can be exciting but it can also make FSA a bit difficult to describe in exact terms. FSA explores what it means to be a school, to engage with architecture, and to pursue peer-to-peer exchange. The point is purely to bring a diverse group of people together without production as a goal. Instead, we think that there is something productive in this connection and the discussions it encourages.

FSA takes a maximalist and inclusive approach; this has the advantage of allowing us to connect seemingly different people and projects who might never have met, and between whom unexpected collaborations start to happen. It attempts to bridge the gap between academia and practice and allow the space for conversations about architecture that are often overlooked. This maximalist approach means that there will be some unavoidable confusion as a result. We focused on growth and development of participants over clarity to outsiders. Still transparency was a constant topic of conversation and a goal for us as the organizers, and we realize that this is an area we drastically need to improve.

At the core are a few aspirational (and perhaps naive) values that we hope FSA can act as a testing ground for, no matter how the program evolves in the future:

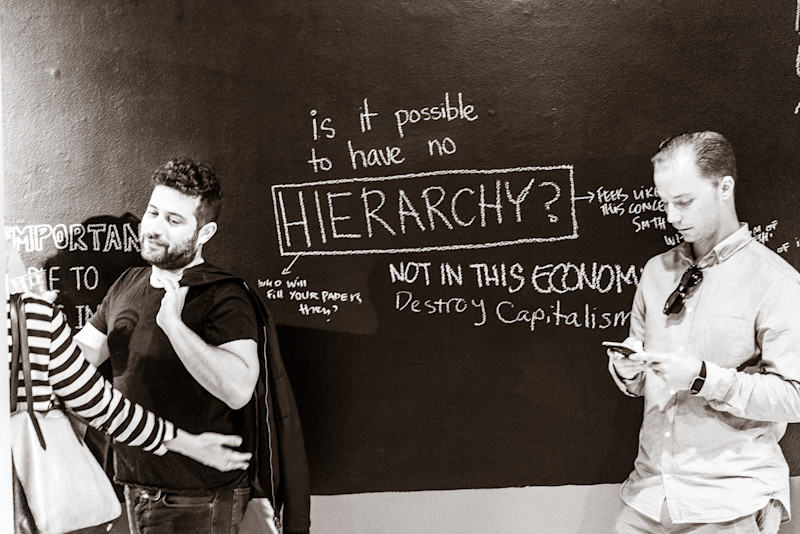

- - Non-hierarchy

- - Interdisciplinarity and inclusivity

- - Freeness(free from constraints of academy and practice, tuition-free, free to be silent or to question)

Leo:

How did you structure things in 2018? Were there instructors and students, or did every participant take on a range of roles in relation to one another?FSA:

We sought to challenge the typical hierarchy of a school and emphasize the value of those attending by removing the impetus on the ‘teacher and student’ relationship. We purposefully avoided using those terms. Everyone involved became a ‘participant.’ This began with the application process. Anyone could apply to be a participant by writing a statement and demonstrating experience engaging with a form of practice relevant to architecture. Then, those who wanted to could also submit a teaching proposal. Not all participants had to host a session, but those who did were also there to listen to others.

This included the organizers—we also submitted our own application statements. This was important because the second stage of admissions was peer-evaluation. We sent each applicant three other essays to respond to in order to be accepted. Some responses were funny, some were graphic, while some wrote long, thoughtful reactions. Here is one example. Most importantly, it generated a dialogue before the school was in session and set the tone for what was to come.

Leo:

What do you think you took away from the challenges and advantages of being a more "horizontal" organization?FSA:

The structure and organizational model was a huge learning experience for all of us. It had some incredibly powerful results, including a truly non-hierarchical working dynamic between the four of us that enabled unanimous decision-making and open discussion. We shared responsibility for almost every aspect of the organization. To do this productively took time, discussion, and trust. It is certainly not the most efficient, but we believe in its benefits over this downside.

Despite our intentions as organizers to make the program itself non-hierarchical, it became difficult for us to blend into the participant group and separate ourselves from those roles as we attempted to hand over the torch. The incredible complexity of running a school and the huge amount of admin work involved proved almost impossible to part with. This is an area that we plan to focus on in the future. In many ways we did too much, and further iterations of the school may reimagine it with more flexibility and with a more established system for handing off responsibility.

Leo:

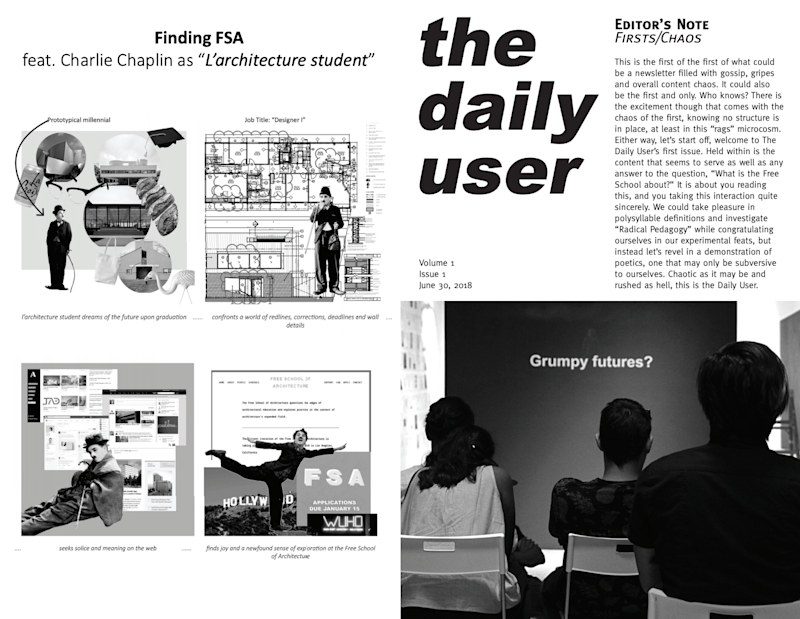

It was wonderful to see so much honest experimentation happening. There was even a publication called the "Daily User," which opened with the lines: "This is the first of what could be a newsletter filled with gossip, gripes and overall content chaos. It could also be the first and only. Who knows?" Can you describe the atmosphere that produced experiments like that one?FSA:

There is something wonderful about a complete lack of enforced output in an inspirational environment. It allows room for playfulness and failure and an opportunity to create for the sake of creating. All the sessions brought something unique to the table, and while we could have allowed more time for making and responding to these, in themselves they provided a backdrop for creative output and an opportunity to make a wider comment on what it all means in the context of architecture.Leo:

It feels like as an alternative and cooperative project, FSA offers a useful space for talking about the limitations of more permanent institutions and the precarity that a lot of designers experience in their relationships with formal education and work experiences. Was that a theme that came up last summer? FSA:

There was a lot of talk of the difficulties of entering practice after education and the effect it can have of burnout. In fact, the first summer almost felt like therapy for architects, bringing together many people who felt disenchanted with the industry. We wanted to actively avoid this in 2018, and focus instead on what needs to and can be done.It is so important to continue having productive conversations around architecture, its impact on our cities and the wider issues affecting communities. It was crucial that FSA engaged with organizations seeking alternative practice models and ways to tie their education and personalities to their work. It was also a must that we collaborated with quirky or playful attempts to understand architecture or the city - the freedom to have fun with ideas is so often missing in both work environments and contemporary education.

Leo:

Has working on Free School of Architecture offered ways to share knowledge with other groups thinking about alternative education?FSA:

We are only one example of many types of alternative educational initiatives arising, in the architecture education world but also in the art world, as education becomes increasingly more expensive and continues to perpetuate the agenda of those with cultural power and capital. We have been in touch with other schools with similar intentions, like Utopia School, Learning Gardens, and Aformal Academy, and there is an incredible opportunity to develop a kind of global network of knowledge and ideas exchange. Eventually, we would like to compile a “Free School Tool Kit” to allow others to run similar events and build on what we have learned so far.

In fact, we used are.na throughout the summer as part of this same intention towards knowledge sharing. We wanted it to be both a resource for participants but also a growing archive to document the summer in the hopes that it might be interesting or useful to others. It still needs another layer of editing and uploading in order to work as a full archive or tool kit, but it did act as an ongoing platform for exchange at the time. Hopefully in the future we can continue to use it as a way for non-participants to engage as well.Next up, we (the organizers) are traveling to the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany to take part in their “Parliament of Schools,” along with others from around the world, including Public School for Architecture, Open Raumlabor University, and many more. It should be a fantastic occasion to engage with and learn about other organizations and explore the future of pedagogy within the architectural field. We’re very excited about how it might influence what we do next!

You can find documentation of FSA's 2018 edition in the channel below, and much more ephemera on the Free School of Architecture profile.

Are.na Blog

Learn about how people use Are.na to do work and pursue personal projects through case studies, interviews, and highlights.

See MoreYou can also get our blog posts via email