Essay

When It Changed Part 1: Before the Billboard Ban

1/7/2020

David Reinfurt

This piece is part of a three-part series called “When It Changed,” originally published in the Are.na Annual. You can read part two and three on the blog as well.

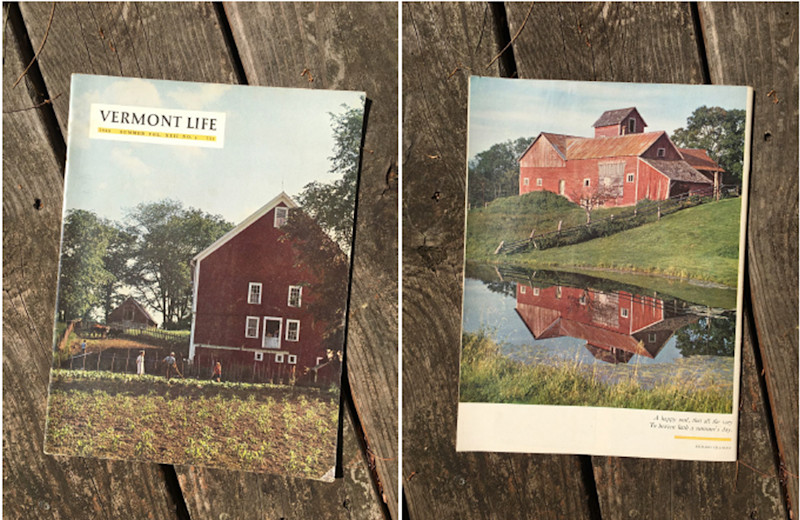

It was 2018, just before the end of summer, and I was in Post Mills, Vermont, paging through old copies of Vermont Life magazine. My wife’s mother and father, longtime state residents, have saved copies of the magazine from the last 50 years or so. It’s published quarterly, each issue taking advantage of Vermont’s four crisply rendered seasons. A story might detail the comings and goings in the town of Corinth around a furniture maker’s workshop at the start of fall, or the raising, in early spring, of a round barn in Bradford. Each story is particular, and somehow each is also generic.

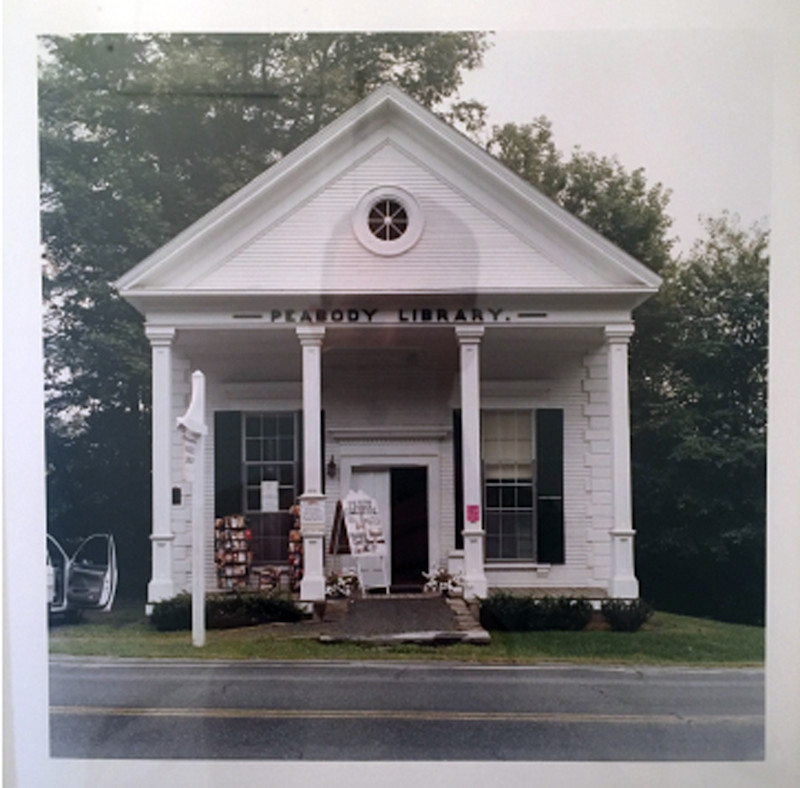

To read the magazine now in a small town in the state is like stepping into a time-shifted mirror. The towns of Vermont Life in 1968 look more or less like the current town of Post Mills. Like any one of the featured places, Post Mills is tiny (population 346) and picturesque. There’s an airport for small planes, gliders, and hot air balloons, a baseball diamond, a graveyard, a farmstand, a general store, and a small public library with a paperback lending rack on the porch. Corinth is 12 miles northwest, Bradford is 13 miles northeast, and in between is unblemished landscape.

I was flipping through the summer 1968 issue of Vermont Life when I was stopped by a small news item included on the last page. It read:

In spite of such pessimism, and similar doubts expressed by Samuel Ogden (page 16), it is possible a shining triumph will have been enacted when these words reach the reader. We’re speaking of Theodore M. Riehle’s proposal to ban all Vermont billboards and signs. Only signs allowed would be standard, state-owned directional signs, and the owner’s on-premises signs. At this writing, in January, Mr. Riehle’s bill, impossible as it seemed at first, appeared to have a good chance of passage.

The tone was surprising and compelling. It seemed to be both a report on what had happened as well as a rather self-assured prediction of what would be soon to happen: a shining triumph will have been enacted when these words reach the reader. Further, from my comfortable position in 2018, I knew the prediction was correct.

I recognized this future law as what would become the 1968 State Billboard Act (Title 10, Chapter 21, § 495). The statute prohibits the construction of all off-premise commercial signage in the state of Vermont and regulates the size and design of all commercial signage. It’s an exceptional piece of legislation and a testament to the power of government regulation to attack problems that are too large or unwieldy to be solved another way. Visiting Vermont today, it’s visually striking to drive through a landscape untouched by commercial signs, or be in a public space without the clamor of so many advertising messages competing for your attention. The reclaiming of public space for the public in 1968, not to mention still, 50 years later, seems an impossibly optimistic action, usefully out of step with what has become the defacto trade of advertising for access that fuels our collective notions of public space in the United States today.

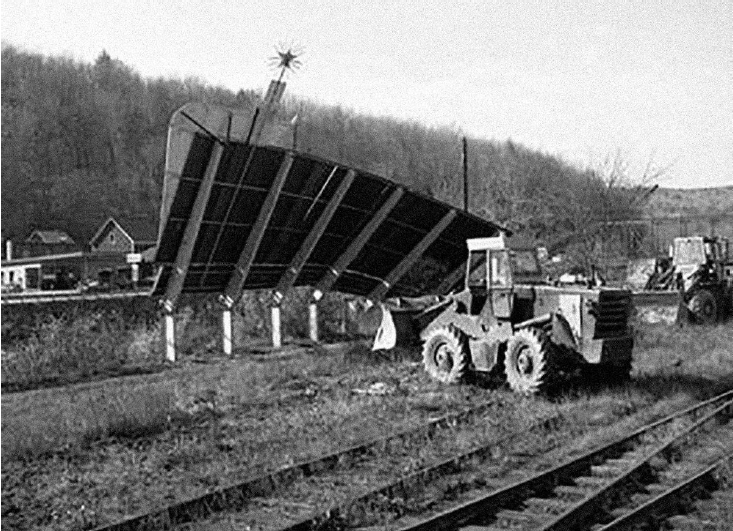

After the law passed in 1968, all billboards were immediately rendered illegal. Those that currently stood were demolished and all future billboard construction was prohibited. Today the law remains and is still rigorously enforced. Happening on this news item, knowing its outcome, understanding its impact, my mind buzzed with the possibility of standing again at that temporal precipice in January 1968, at the time of writing, when the future was not yet decided but it felt like something big was about to happen.

The architect of the billboard ban, Theodore M. Riehle, moved to Vermont in 1952. Ironically enough, a billboard is what brought him to Lake Champlain in the first place: After selling the Master Rule Company in New York, he spotted a road-side advertisement for waterfront property for sale. One of the properties was a remote island off the coast of Grand Isle previously run as a subsistence farm and, perhaps appropriately, named Savage Island. There were no mainland connections on Savage Island; no electricity, no water, no sewage, no garbage, and no bridge. Riehle paid $5,500 for the property and lived on the island for the next 56 years, until he died in 2008.

Life on Savage Island was not simple. Solar- and water-generated electricity was meticulously conserved. Going to the grocery store required either a boat, an airplane, or, at times, a treacherous hike across a frozen Lake Champlain. Riehle swam twice a day when the weather permitted (always naked), and maintained a flock of sheep and the upkeep of a 207-acre island. By 1968, Riehle had been recruited to become a junior state legislator, a job that required him to spend days in session at the capital in Montpelier. Those days, Riehle woke up at 5 a.m., swam, flew his daughter to school in Burlington, then drove to Montpelier to be in his office by 9.

Riehle was an outlier and a contradiction. He was a skinny-dipping Republican in an overwhelmingly Democratic state who lived off-the-grid, raising sheep, swimming, and sailing on his own private island. But he was also a vigorous defender of the environment (the public realm) from the exclusive interests of private enterprise. Republicans rarely agreed with him. He was a committed capitalist whose best-known legislation was essentially socialist. He lived away from society but was concerned with the public commons that are shared with all of his fellow Vermonters. He recognized that the beauty of the state’s natural environment was perhaps its greatest resource—and he intended to keep it that way.

Passing the law was not easy, but Reihle leveraged these apparent contradictions, aided by his significant charisma. From the right side of the State House aisle pushing what would be a more conventionally left agenda, he garnered the full support required to pass the billboard legislation. Vermont remains billboard-free.

At home in New York City, I get the newspaper delivered every morning and read it with breakfast. It’s an anachronism, perhaps even an affectation at this point. While in Vermont, I skip the newspaper, and by the end of August 2018, I hadn’t been paying much attention to the news in any form. On the morning of August 22nd, after biking down to Baker’s General Store, I caught a glance of the New York Times front page screaming its headlines at me ACROSS ALL SIX COLUMNS. I recognized it immediately as an extraordinarily rare headline treatment, reserved for only the most important news—war, national disaster, or, as it turns out, the indictment of a Presidential counsel. The headline read:

PLEADING GUILTY, COHEN IMPLICATES PRESIDENT

The photograph printed below catches Michael Cohen’s face leaving the courthouse — he looks stunned, but also stares straight ahead at the unknown future, towards the domino effect that his actions may yet help put into motion.

To the immediate left of the photograph was another bit of (good) news: the conviction of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign manager, Paul Manafort. Finally, another front-page headline described the net effect:

A ONE-TWO PUNCH PUTS TRUMP BACK ON HIS HEELS

I was struck by the combination of news items collected on the front page. It felt a lot like coming across that news from the Green Mountain Post Boy in a Vermont Life magazine from 50 years ago. I recognized the feeling once again, and the look on Cohen’s face seemed to mirror it: like the Vermont Life billboard law news item, this might be the moment just before things change.

David Reinfurt is 1/2 of Dexter Sinister, 1/4 of The Serving Library, and 1/1 of O-R-G inc. Dexter Sinister started as a small workshop on the lower east side of Manhattan and has since branched pragmatically into projects with and for contemporary art institutions. The Serving Library publishes a semi-annual journal, maintains a physical collection, and circulates PDF texts through its website. O-R-G is a small software company. David currently teaches at Princeton University and his work is included in the permanent collections of Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum, Museum of Modern Art, Walker Art Center, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. David was the 2016-2017 Mark Hampton Design Fellow at the American Adademy in Rome.

Are.na Blog

Learn about how people use Are.na to do work and pursue personal projects through case studies, interviews, and highlights.

See MoreYou can also get our blog posts via email