Essay

When It Changed Part 2: The Continued Corporatization of the Web

1/7/2020

Eric Li

This is the second installment of a three-part series called “When It Changed,” originally published in the Are.na Annual. Read part one here.

Meanwhile, while David was in Post Mills, Vermont, I was in New York City. On August 22, 2018 I flipped over the New York Times and found, well under the six column headline (PLEADING GUILTY, COHEN IMPLICATES THE PRESIDENT) and just below the fold, more “good” news:

FACEBOOK SAYS NEW CAMPAIGNS TRIED TO SPREAD GLOBAL DISCORD

It may not have been the most pressing news of the day, but the story reported on an alarming addition to the previous news that Facebook had played a pivotal role in amplifying divisive messages ahead of the 2016 U.S. elections. Now, Facebook was claiming to have identified and removed 652 fake accounts, pages, and groups attempting to spread misinformation — not just in America, but around the world. It wasn’t yet entirely clear to me how extensive this misinformation was on the platform which, by this point, connected almost 2.3 billion users, or nearly 1 out of every 3 people on the planet.

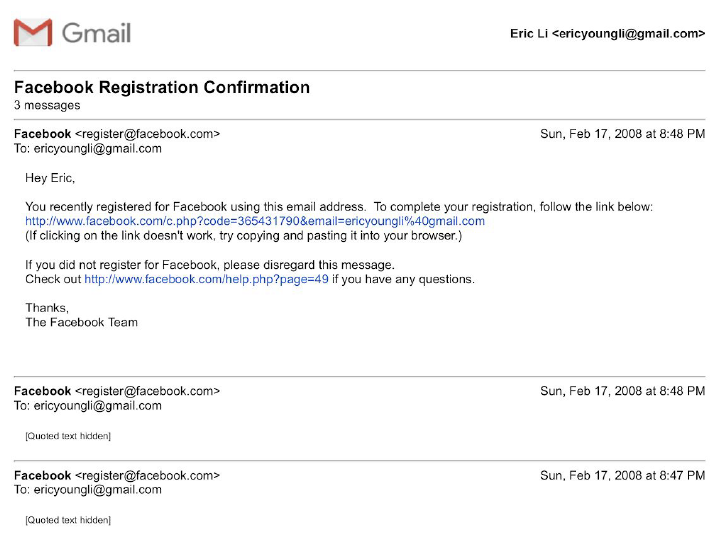

This is not what I signed up for when, as an eighth grader, I created a Facebook account in 2008. Sitting in my apartment, I found myself coming back to this (relatively) small news item. How did one Internet company come to permeate our daily lives, affecting not only our social interactions with friends, but also who our presidents are?

To understand how we got here, we have to trace back to the very origins of the Internet, before terms such as “attention economy,” “echo chambers,” and “filter bubbles” even entered the public consciousness.

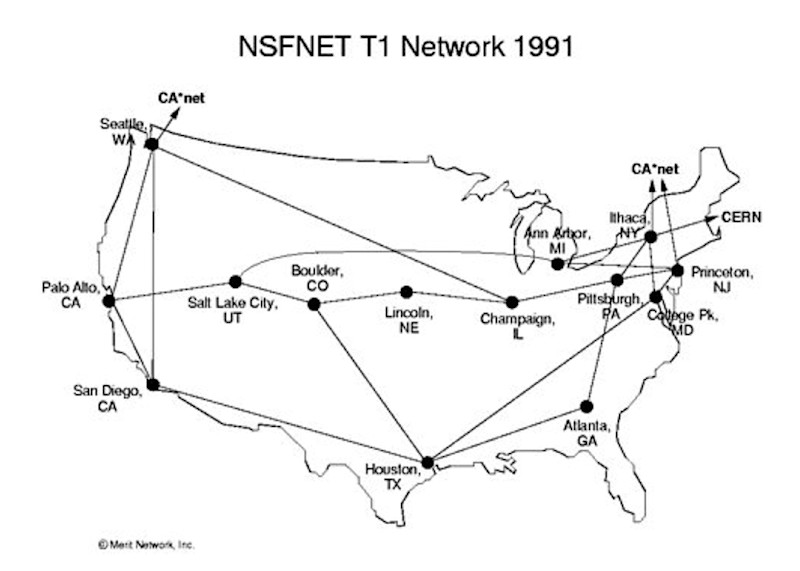

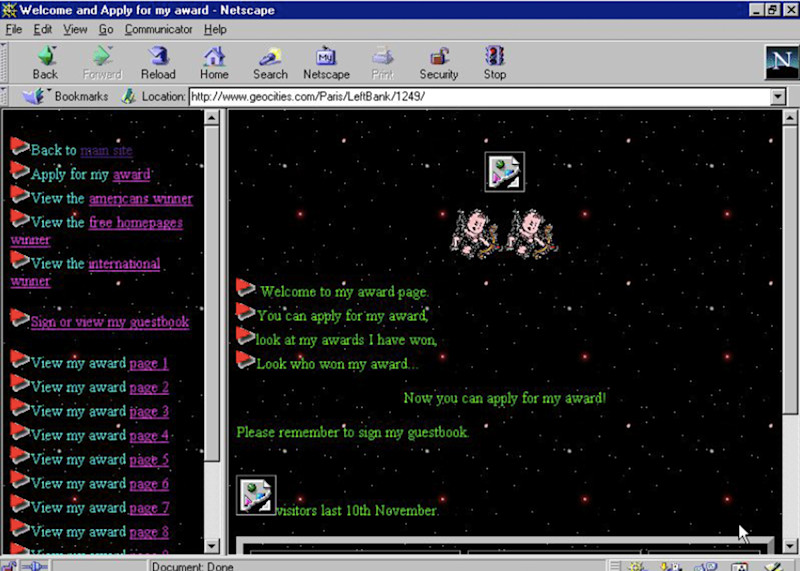

It was 1969, and the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency had just put into practice a concept two years in the works: ARPANET, the packet-switching network that foreshadowed the internet. ARPANET initially connected four university computers over a distributed network and was used by researchers to share scholarly information before it eventually morphed into a commercialized service that any person could buy access to. The creation of early web browsers such as Mosaic (around 1993) provided a visual interface for the Internet, which in turn gave anyone with a personal computer the ability to access the network. This early internet, now often referred to as WEB 1.0, was characterized by a passive consumption of information: Websites popped up as general purpose information guides, and static web pages such as Geocities personal websites offered a place for individuals to exist in the new frontiers of cyberspace.

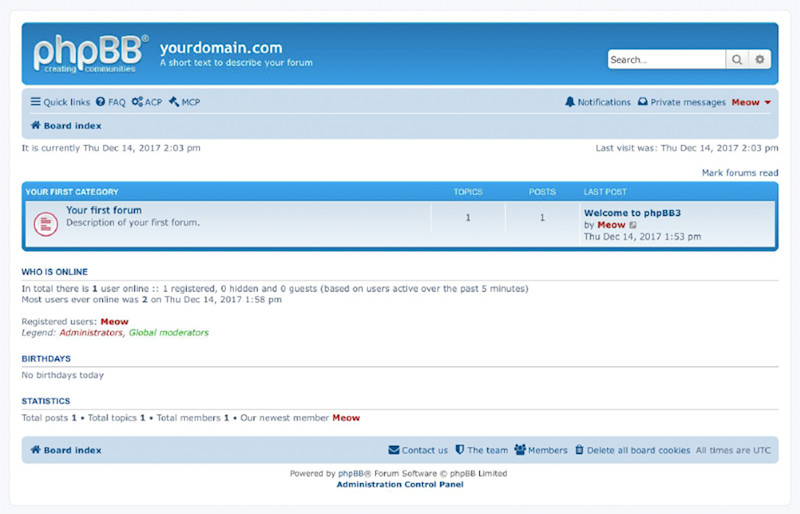

Because the way that we consumed content was different in the early ’90s WEB 1.0 era, the way we thought about content was different then, too. Visitors would leave a note in a site’s guestbook to mark their presence, with no expectation of a response. Comment threads in websites didn’t exist yet. The first “social networks” of the internet came in the form of services like Internet Relay Chat, one of the first massively adopted softwares for real-time communication, and the proto-internet forums of Usenets, a system of shared bulletin boards where users could leave messages and share files. People used these shared digital spaces to discuss things like their hobbies, interests, or a particular television series.

By the late ’90s, websites had started to include rudimentary social networking features that made them more accessible to more people. You could create a user profile, maintain a friend list, and communicate via chat rooms. Whereas previously, the act of visiting a website and leaving a message was just a feature, it was now the focus of entire platforms. This was WEB 2.0, where the focus was no longer on a passive consumption of information, but on the active creation of content and connecting to others.

In 2003, these new practices converged around Myspace. It was a platform much like previous forums and chat rooms, with one significant exception: users were no longer anonymous. Instead, Myspace’s promise of connecting real friends and past acquaintances encouraged people to use their actual names and upload photos of themselves for their profiles. In the process, it normalized the loss of anonymity on the web.

Through a series of business missteps, Myspace eventually turned into more of an advertisement platform than a social one. In 2004, its popularity was eclipsed by a new social network. THE FACEBOOK had started out as a platform for students at elite colleges to make “friends” before branching out into all colleges and high schools and eventually becoming available to everyone (losing the “the” in the process). A little over a decade after Internet users were anonymously signing website guestbooks, Facebook now offered a digital feed where your actual friends could leave messages, see what others had written, and participate in threads with other friends. What made Facebook and the social networks that succeeded it so successful was a “network effect,” a term that suggests that the perceived value of a platform increases as more people in your real-life, physical network join. Social networks became a combination of the digital and the physical, creating a public realm that encompasses both our “real-life” surroundings and the virtual.

Facebook today is not what it once was. These days, I can barely make out which posts are by people and which are by social media specialists (a job position that owes much of its existence to the platform). While it still has all of its earlier social sharing and communication features, every digital inch of Facebook has been infiltrated by corporations, governments, and organizations clamoring for my attention. Campaigns such as #DeleteFacebook following the Cambridge Analytica scandal have reduced the once daily posts by my friends to perhaps a profile picture update once a year. I’d hardly call it a “social network” anymore.

So what is it? A friend of mine once referred to Facebook as a utility, which struck me as an apt descriptor. It’s a utility in the economic sense: the company’s internal algorithms determine what to serve up in order to provide us with the most satisfaction. It’s also a utility in the public good sense. For many, Facebook is the Internet. In fact, in 2017, the company even got into hot water with government regulators in India when it’s purported Internet for All campaign (which aimed to provide Internet as a universal human right) in fact only granted users access to Bing and Facebook, not even providing access to email. Facebook users can get their news, keep in touch with loved ones, buy products, and more, all within the platform’s digital walls. The question is, who is it a utility for? I imagine not us.

The company’s internal cultural motto to “move fast and break things,” described in a New Yorker article as “youthful insouciance,” has resulted in too quick a progression and too many things broken. One massively broken thing is the manipulation of the platform by motivated governments and companies to influence the 2016 presidential election and sow seeds for global discord. In the same New Yorker article, titled MARK ZUCKERBERG’S APOLOGY TOUR, the author writes, “It’s now clear that the problem wasn’t the selfies; it was the business model.” That business model is predicated on sifting through its billions of users’ personal data to provide advertisers with valuable access to their exact target audience. It relies on people visiting the platform, which is why Facebook’s “feed” is a never ending source of constantly refreshing information, constructed by algorithms that are designed to keep us coming back for more. This interface, addictive by design, might be considered the billboard of the digital realm. Once occupied mainly by status updates and images of friends, our feeds are now an incoherent stream of promoted news sources, advertisements, and posts by people we don’t know.

Because these digital “billboards” are informed by mountains of user data, they can be a lot more precise than physical ones. This was the basis of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which landed Facebook on the same front page as the indictment of a Presidential counsel. By promising to “microtarget” specific individuals, Facebook was also able to provide a utility for the data analysis firm Cambridge Analytica to target people by political affiliation and manipulate national and world events.

In a 2015 speech in Washington DC, Apple CEO Tim Cook said, “We believe the customer should be in control of their own information. You might like these so-called free services, but we don’t think they’re worth having your email, your search history, and now even your family photos data-mined and sold off for god knows what advertising purpose. And we think someday, customers will see this for what it is.”

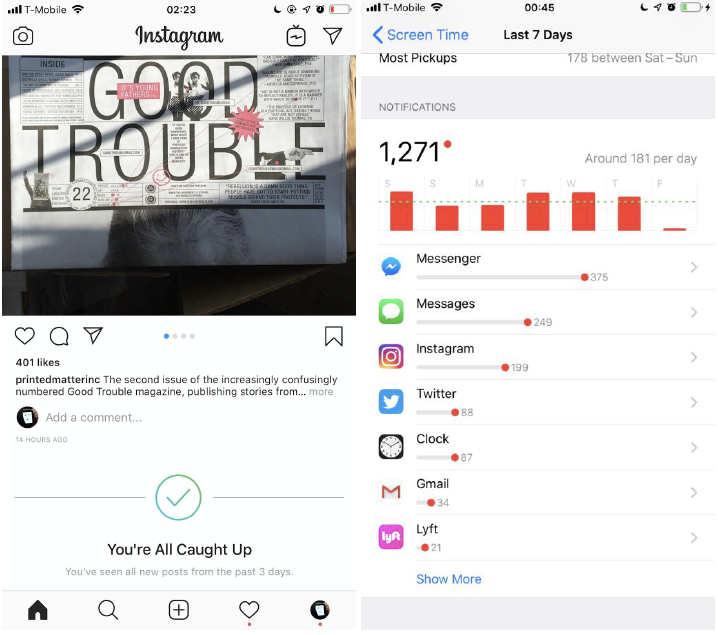

Perhaps we’re approaching that day now. Every other day, I see a post from a friend announcing that they’re taking a break from social media. And social platforms have started to take notice: Instagram now lets us know when we’ve seen all new posts in a certain time period, actively discouraging users from addictively scrolling through its “feed.” In Apple’s latest iOS mobile operating systems, a feature called Screen Time provides a set of in depth tools for understanding and limiting our screen usage (a similar feature exists in Android). A dashboard lets you view the number of notifications you get, see how much time you spend in each app, and even allows you to set limits for phone use.

These features, as ironic as it is that they are being created by the same companies that are largely responsible for our addiction to phones and social media, indicate a significant inflection point. It seems that we’ve finally begun to sober up from some long digital soup induced stupor, and things are finally about to change.

Eric Li is a graphic designer and software developer based in New York. He graduated with a BA in computer science and visual arts from Princeton, where he was the 2018 recipient of the Jim Seawright Award in Visual Arts. Current and past collaborators include O-R-G, LUST, Google Design, and IDEO. Eric was also the designer for the Visual Arts program at Princeton from 2018–2019. With Nazli Ercan and Micki Meng, he runs Friends Indeed Gallery in San Francisco. Eric has been invited to guest lecture at Princeton, SVA, and UPenn. He currently works at MoMA.

Are.na Blog

Learn about how people use Are.na to do work and pursue personal projects through case studies, interviews, and highlights.

See MoreYou can also get our blog posts via email